On Classifying Marsupials

When I was a kid, pretty much every zoology book I signed out of the library divided mammals (aka the class Mammalia) into 19 or so orders — 17 placental (giving birth to fully developed and gestated offspring — i.e., carnivores, rodents, cetaceans as in whales); one monotreme (giving birth to eggs — i.e., platypi and echidnas); and one marsupial (giving birth to what are basically still fetuses, which soon tend to wind up in their mother’s built-in pouch). But sometime between then and now, the order I’d long enjoyed as Marsupiala was upgraded to an “infra-class,” itself split between Australidelphia (mostly Australian marsupials) and Ameridelphia (all the American marsupials except one), and containing what are now seven discreet orders (which I’ll specify here in a little bit.) Total orders of non-extinct mammals now number 29 — a more than 50% increase from the quantity I grew up with. Blindsided by this taxonomical equivalent of Pluto not being a planet anymore or Negro Leaguers finally being recognized as the major leaguers they always should have been, I naturally wondered what the heck happened. So I opted to dig deep.

For all I know, indigenous peoples of the deep global South had been classifying marsupials in their own way for thousands of years — in the large island continent ultimately named Australia especially, after all, there were barely any other mammals available to classify. But Jack D. Burke of the Medical College of Virginia Anatomy Department lists no such aboriginal schematic in his 1968 MCV Quarterly essay “A Brief History of the Taxonomy of Mammals,” which starts its story with Aristotle, 688 B.C. Assyrian inscriptions and Leviticus 11: 1-47 (the verses about which domestic mammals and birds of prey and lizards it’s okay to eat and which will leave you unclean until sundown.) So for our purposes, let’s just acknowledge that marsupial classification as we know it might never have happened had explorers from Holland not landed down under in 1606. In the next century or so, enough Dutchmen had navigated to southern Australia to colonize it as “New Holland” (not to be confused with “New Amsterdam,” which is southern Manhattan instead.) By 1690, people were describing mammals with snuggly baby pouches as “marsupial,” from the Greek marsupion, meaning pouch, bag or purse.

In the 1758-published tenth edition of his landmark Systema Naturae, Swedish doctor and biologist Carl Linnaeus named the class of hair-covered quadruped vertebrates who feed milk to their young Mammalia; as Londa Schiebinger pointed out in her 1993 American Historical Review article “Why Mammals Are Called Mammals,” gender politics of the day were clearly a factor — especially since, when you think about it, only half of all mammals have mammary glands. “It has been said that God created nature and Linnaeus gave it order,” Schiebinger wrote. “Carolus Linnaeus, also known as Carl von Linné, ‘Knight of the Order of the Polar Star,’ was the central figure in developing European taxonomy.” The “binomial” practice of giving every living and once-living thing a Latin genus and species name? That was Linnnaeus’s idea. Systema Naturae‘s tenth edition, Burke says, “is taken as the zero point for zoological nomenclature.”

And what order(s) he gave! He divided mammals into eight, focusing on how many teeth they had, where those teeth were, and how they worked — the first person to attempt such a thing. Marsupials were not one of those eight yet, apparently at least in part because Australia hadn’t been explored much, though Linnaeus did put Western Hemisphere opossums of the family Didelphis into the order Bestiae, along with armadillos, hedgehogs, moles, pigs and shrews.

The year British Royal Navy Captain James Cook set sail for the East Coast of Australia, 1770, was not coincidentally also the year that Guugu Yimithirr-speaking natives of the future Far North Queensland bequeathed to the English language “gangurru,” their name for the species now called the Eastern grey keangaroo. (Contrary to persistent myth, the word did not actually mean “I don’t understand the question.”) “Marsupial” graduated from mere adjectival description to a noun around 1805 (see “heavy metal” circa 1970 or so), and six years later in Prodromus systematis mammalium et avium Germany’s Johann Karl Wihelm Illiger named Marsupiala one of 39 families within his 14-order overhaul of Linnaeus’s chart, filing most of them under the order Pollicata along with non-human primates (Homo sapiens had its own order, Erecta); kangaroos and potoroos were separate, in an order called Saliente.

That was 1811. Étienne Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire and Baron Georges Léopold Chrétien Frédéric Dagobert Cuvier, who as you might guess were French, had apparently published their own first draft of mammal taxonomy in 1795. But Cuvier’s greatest hit was Le Regné Animal in 1817, which Burke reports “became as popular as Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae” almost six decades before. As with Illiger, there were 14 Mammalian orders, but this time Marsupialia — including opossums, true phalangers, flying phalangers, potoroos or kangaroo rats, kangaroos, koalas, dasyurus (quolls) and phascolmys (apparently wombats) — was one of them.

But here’s where it gets more confusing — or maybe it’s just that it took 19th Century zoologists a while to catch on. In his 1835 Natural History and Classification of Quadrupeds, William Swainson, Esq. (“Honorary Member of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, Fellow of the Royal and Linnean Societies, Etc.,” not to mention a guy who thought mammals “are no less remarkable for the complexity of their organisation and their great bulk than for their importance to mankind,” by which he means God has given them to us to help till and cultivate His dominion earth) organizes marsupials all over the map: opossums with the prosimian primate the galago or bush baby for their long hind legs (which to get even more confusing he parallels avian-wise with big-footed Australian lyrebirds and Southeast Asian/north Aussie/Pacific Islander Scrubfowls); “dasyuri or brush tailed possums” (quolls again I think) with carnivores; “the dog-faced opossum, recently designated as the type of the genus Thylacinus” (later referred to as the Tasmanian tiger or wolf and last seen alive in 1936 though cryptozoology websites on whom it’s a sort of mascot wish otherwise) at a midpoint between Canis (dogs) and Felis (cats) (also carnivores); Dasyurus ursinus (later called the Tasmanian devil) somewhere between bears and thylacines. The latter two beasts inhabit Van Diemen’s Land, 1825-1855 original colonial name for the island off Australia’s southeast coast that provided a title for a 1988 U2 song.

In the early 1860s, American geologist-etc. James Dwight Dana and Scottish-born (but an American resident of New Harmony, Indiana since he turned 18 in 1928, the year after his dad’s planned utopian “community of equality” there tossed in the towel) geologist-etc. Richard Owen both did a thing where they grouped Marsupiala and Monotremata inside a sub-class that Owen calls Lyencephala (meaning “loose-brained”) and Dana called Ooticoids due to their relationship to oviparous (i.e., egg-laying) vertebrates like birds and reptiles, then split eight placental orders into higher (Gyrencephala meaning “convolute-brained” or Megasthenes) and lower (Lissencephala meaning “smooth-brained” or Microsthenes) divisions. Each individual higher order matches a corresponding lower order, like major leagues with farm teams: primates (still called Quadrumana and still excluding people) have bats, carnivores have insectivores, hoofed herbivores have rodents, whales and manatees have edentates (or “brutes”: anteaters, aardvarks, sloths, armadillos, pangolins.) Dana, especially, really believed in pecking order, with Man standing above it all and marsupials, well, down under.

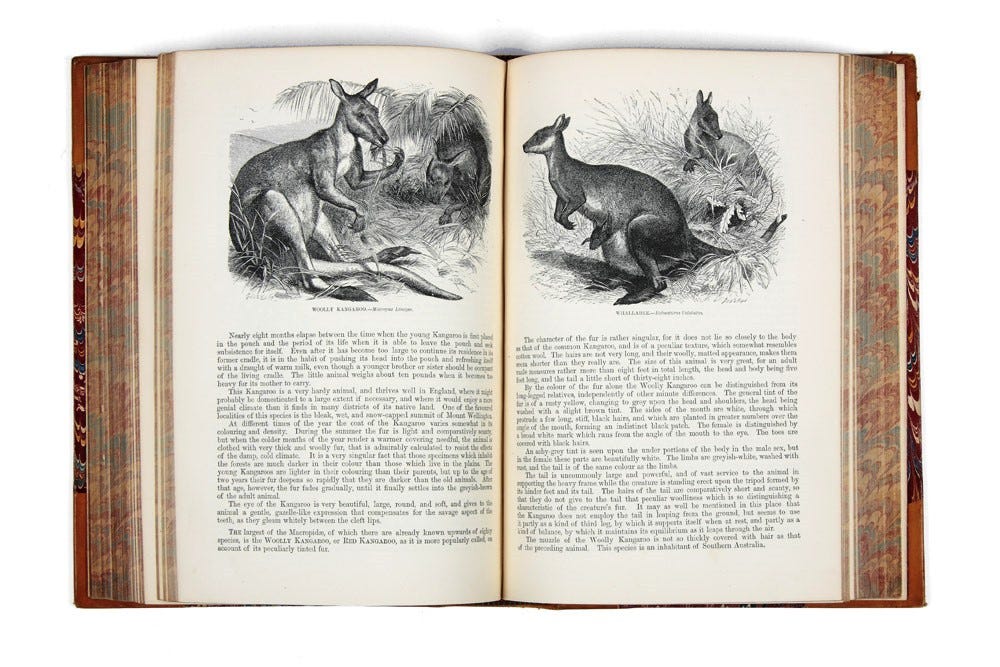

And the pecking order got uglier. J.G. Wood’s 800-page, softcover Natural History: Mammallia from September 1890, first American edition, is one of my favorite outdoor flea-market finds ever — Cost me five dollars I think, 10 at most, sometime around the turn of the millennium. Back cover is an ad boasting that “Walter Baker & Co’s Breakfast Cocoa from which the excess of oil has been removed, is absolutely pure and it is soluble.” Inside front and back covers are both ads for books introducing this new-fangled technology called “electricity.” Wood devotes 47 pages to marsupials: “The extraordinary animals which are grouped together under the title of Macropidæ are, with the exception of the well-known opossum of Virginia, inhabitants of Australasia and the islands of the Indian Archipelago.” So far so good, plus lovely and realistic animal drawings on almost every page (the numbat is labeled “Myremecobius” — lots of recent discoveries are known only by scientific names) and far-from-objective descriptions like “The Tasmanian Devil seems to be diabolically devoid of gratitude, and attacks indiscriminately every being that approaches it.”

But then you stumble onto a page where J.G. Wood talks about human beings. At the end of the marsupial chapter, he wonders why there are no (still not called) primates on the antipodal continent: “Australia appears to be a country that would be well adapted for the monkey race,” he writes. “Yet, as far as it yet known, there is no member of the quadrumana to to be found in that land.” Upon which he starts discussing the native people: “In truth, the aboriginal Australian is so low a type that there seems to be little necessity for the existence of the quadrumana race to prevent too abrupt a transition from the bipedal to the quadrupedal form.” Earlier in the book, while discussing why zoologists are right not to classify humans with apes, he asserts that even the southern African bushman (“one of the lowest and least developed of human beings, probably the lowest of the human race”), despite his “very pigmy” stature and musculature, stands “infinitely higher than the gorilla, “one of the most dull and stupid creatures imaginable.” Oof — A reminder that naturalists of the time were often committed to charting human subtypes as well (both Linnaeus and Culvier did), and weren’t above assigning or at least suggesting racist hierarchical rankings.

It became customary through the 19th Century to divide Mammalia into three sub-classes: Ornithodelphia (“bird-uterus” monotremes), Didelphia (“two-uteri” marsupials) and Monodelphia (“one-uterus” placentals) for Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1834; Prototheria, Metatheria and Eutheria (same breakdown, more explicitly hierarchical) for Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880. Star paleontologist and Columbia University zoology prof George Gaylord Simpson retained Huxley’s holy sub-class trinity when he published The Principles of Classification and A Classification of Mammals in 1945, cataloguing 14 extant and nine extinct Mammalian orders. Three groups he considered sub-orders — Duplicidentata a/k/a Lagomorpha (rabbits and hares), Pinnipedia (seals and walruses) and Pholidota (pangolins) — had been widely upgraded to orders by the time I was old enough to obsess on such trivia.

Up to this point, classifications seem to have been based largely on physical structures of animals’ body parts — superficial at first, then increasingly detailed dissection of anatomical systems, but for the most part similarities and differences visible to the naked or at least microscope-equipped eye. But recent decades have been marked by increasing use of what’s called phylogenetics — that is, data-processed analysis of DNA and amino acid sequencing to construct family trees of common ancestors heading backwards in time and thereby better determine degrees of separation between related organisms, with way less emphasis on ranking species in terms of supposed perfection. In the marsupial sector, these advances seem to have been most conclusively charted in “Recent Advances In Material Systematics With a Syncretic New Classification,” a 1987 paper by Australian vertebrate-systematist/anatomist/ paleontologist/ archaeologist and survivor of myriad tropical diseases (until his death at 61 in 2019) Kenneth Peter Aplin and New South Wales paleontology professor Mike Archer, whose hobbies include regularly debating creationists and attempting to clone the thylacine. All the new orders mainly have those two to thank.

Which seven marsupial orders are, now, as follows: Didelphimorphia (American opossums); Paucituberculata (pouchless South American so-called “shrew opossums” or “opossum rats” of the genus Caenolestes); Microbiotheria (the South American creature known as monito del monte or “colocolo opossum,” which is the only New World member of the superorder Australidelphia rather than Ameridelphia, which means its ancestors probably crossed hemispheres via the future Antarctica back in Gondwana supercontinent days more than 180 million years ago); Notoryctemorphia (marsupial mole or, in indigenous Australian dictionaries, itjaritjari or kakarratul, both of which look really fun to say); Dasyuromorphia (meat-eating Australian marsupials: thylacine, Tasmanian devil, mouse-sized dunnart, cat-sized quoll, lovely reddish-brown banded mini-anteater the numbat); Peramelemorphia (bandicoots and rabbit-eared bilbies); Diprotodontia (155 species: kangaroos, wallabies, wallaroos, potoroos, Australia possums without the initial “o”, beloved koalas and wombats). All order names except the marsupial mole’s one seem to date back to late 19th Century, when they mere families; the oldest, Diprotodontia, was coined by Richard Owen in 1866.

The late great science writer Stephen Jay Gould, in an essay entitled “Sticking Up For Marsupials” in his 1980 collection The Panda’s Thumb, counters the centuries-old canard that marsupials are somehow evolutionarily primitive, “based on the smug assumption that difference from us is worse” — even their subclass name Metatheria consigns them to a limbo between premammal monotremes and true-mammal placentals, implying they’re “not all quite there.” The main argument in support of this supposition, he says, has been that “marsupial fetuses never developed the essential trick that permits extensive development within a mother’s body”; hence, the extinction of most large South American marsupials, including predators, when the isthmus of Panama rose from the ocean a couple million years ago, thus allowing theoretically stronger-gened Northern placentals to move south and seemingly displace them.

But where past zoologists saw a deficiency, Gould sees a tradeoff: “Placentals invest a great deal of time and energy in offspring before their birth. This commitment does increase the chance of an offspring’s success, but the placental mother also takes a risk: if she should lose her litter, she has irrevocably expended a large portion of her life’s reproductive effort for no evolutionary gain. The marsupial mother pays a much higher toll in neonatal death, but her reproductive cost is small. Gestation has been very short and she may breed again in the same season. Moreover, the tiny neonate has not placed a great drain upon her energetic resources, and has subjected her to little danger in a quick and easy birth.”

Those originally Northern Western placentals such as jaguars, he suggests, might instead have developed a sort of immunity from extinction thanks to two extinction events their ancestors had endured way back in the Tertiary Period of the Cenozoic Era; after all, their gentrification replaced fellow placentals in South America as well. And despite it all, there are still plenty of marsupials around, and more left in South America than most casual observers might guess. On the other hand, just today, after years of forfeiting their habitat to climate-change-driven fires and drought, Australia officially designated koalas an endangered species. Let’s just hope marsupials make it through the Anthropocene — if they don’t, we probably don’t deserve to, either.

Eliminated for Reasons of Space, 11 February 2022

via facebook:

Phil Dellio

In 20 years of teaching natural science to elementary kids, animal classification was really the only topic that interested me (I was okay with stuff like space and flight).

Chuck Eddy

It’s always been an obsession of mine (as I’ve said elsewhere, I’m sure.)

Phil Dellio

I can still rhyme off the 5 kingdoms: animals, plants, fungi, monera, and protista. (No, I didn’t check.)

Mike Freedberg

Well …..

Sara Quell

I wonder if any of the scientists mentioned ever quoted Olivia Newton-John's "I'll Be You a Kangaroo."

Chuck Eddy

Tie me kangaroo up, sport.

Josh Langhoff

Thanks for setting me straight on the origin of “kangaroo.”

Kevin Bozelka

Um, you didn’t RANK them???

Chuck Eddy

This is an anti-animal-ranking piece (as you’ll see when you read it)!

Clifford Ocheltree

Wombats rule!

Kevin Bozelka

Yeah but GRADE those wombats!

Clifford Ocheltree

Kevin, enough that you understand they they rate above all other marsupials.

Kevin Bozelka

ok so A+ then. Thanks for your grade. We will now tally.

Clifford Ocheltree

There can be only one, MINE. Because, when it comes to the animal kingdom I AM always correct.

Steve Alter

This is awesome! That opossum picture is creepy as hell, though.